Sweet December

During the month of December, a deep Christmas spirit erupts to fill every corner of Hanna Niang’s village. The crisp winter weather is a joyous gift after months of heat and rain, and at night, Christmas decorations twinkle in harmony with the sounds of youth caroling from door to door.

Niang’s village lies near the Chin State. The Chin State is home to many communities of Chin people, and you can often find an entirely different language or culture in just the next town over. Niang herself is Zo Chin.

The holiday season begins with a celebration called “Sweet December,” celebrated on December 1st. For Niang’s family, it’s a time to gift and eat sweets, gather at church for worship, and follow the program until the youth take over with activities or lighthearted pranks.

“There’s always a comedian, you know… they might perform, tell jokes. One time I remember the youth asked the pastor to dress in a silly way he never dressed before. We always have a lot of fun,” she says.

The day ends with a dinner of milk tea and sticky rice.

Preparations

According to Niang, celebrating Christmas in the village is much more fun than it is in the city. The village has unlimited space for locals to play music “as loudly as [they] want.” Chin State Christians account for 85% of the 6% of Christians living in Myanmar, so there are plenty of people to join in the celebration (although Buddhists and Muslims are always invited to celebrate in their “own way”).

In the city, there’s less space, more neighbors concerned about volume, and it’s hot.

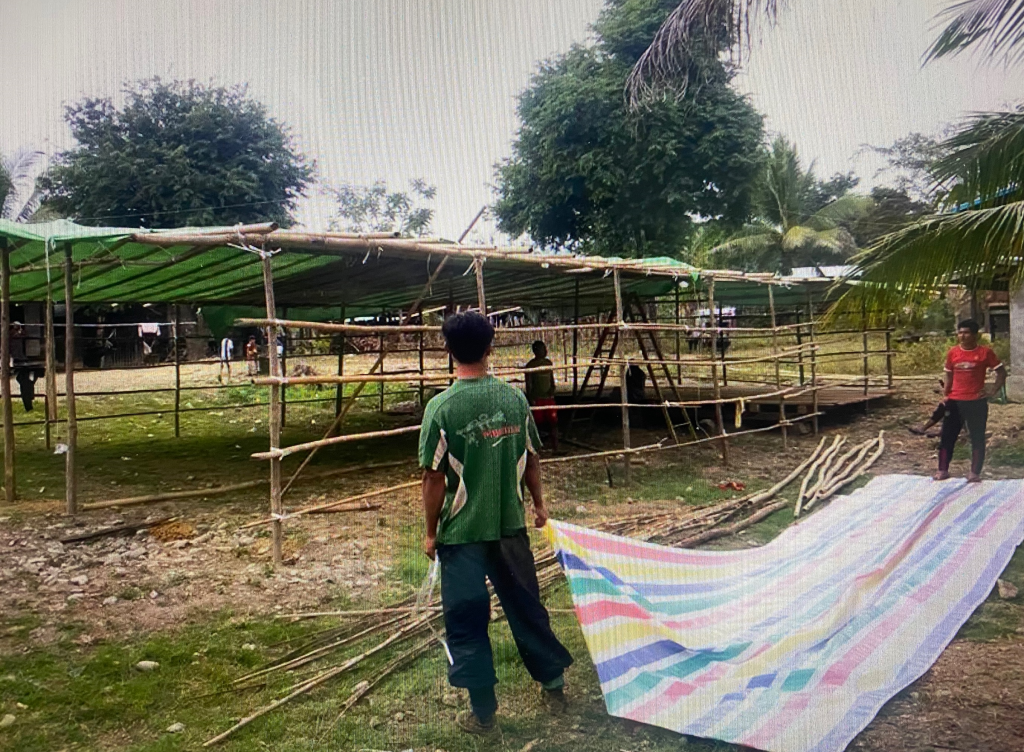

Christmas is celebrated outside. The pastor, elders, youth, and the women’s group of the church begin planning months in advance. Before Christmas Day, the church will construct a large bamboo or wooden frame to serve as a pavilion. Although there’s rarely more than a dusting of snow, dried rice leaves are then used to line the floor, ceiling, and walls, which may also be reinforced with a tarp to prevent eager children from jumping through.

No table is long enough to seat every person, so the church prepares a long wooden buffet where everyone sits and shares their meal. Both are temporary structures which are burned for easy takedown after the event.

Christmas Day

One long road lined with houses stretches the village. On Christmas Day, the houses become shops. Each home offers something different, from traditional food like porridge to chips that are sour, spicy, or sweet. Sometimes owners already have permanent stores in front of their house. Those who want to sell but don’t have a house by the road ask a relative to sell on their property.

“Imagine Avenue of the Cities,” Niang says, “one road with shops that everyone walks on. There’s a lot of conversation about ‘what are you going to do, what are you going to sell.’”

“And if you’re the relative, you might get to eat some of what is being sold,” she gladly adds.

At the event, everyone is treated to both lunch and dinner. Families most often bring their own rice to accompany their food and milk tea. Children often roll their rice into a ball to carry while they play hide and seek. People coming from the Chin State don’t grow rice, so they bring corn instead.

The most famous dish is made from sticky rice cooked in a bamboo stick and grilled on a barbecue.

“Everyone has a different name for it, but Zo Chin call it ‘Bom Dan.’ We have black and brown bamboo, some people will put filling, like red beans,” Niang says.

Between meals, there’s dancing, singing, games, and worship. Lively conversation fills the air from all directions. Everyone is excited to come together, celebrate, and share blessings with one another – not as individuals, but as a community.

From Myanmar to the U.S.

Church members most often choose to divide event costs among themselves, even if they are overseas and not able to join the celebration. Depending on the church’s needs, members may donate drinks, rice, or meat like pork, cow, and ox.

In 2019, Niang’s family took over the costs for their church’s celebration in Myanmar despite living in the States.

U.S. culture is a whirlwind of future tense, and it comes as a shock to those experiencing their first Christmas after resettlement. With everyone thinking hours, days, even weeks ahead, lively celebration is replaced with small, formal service; Christmas is celebrated with immediate family rather than the community as one. Few have time to stay and chat, let alone celebrate through the night.

“When we celebrate, we celebrate as a community, with community.” Niang says. “Here, we’re thinking about work instead of celebrating. And another thing is gifts.”

Gift giving isn’t nearly as central in Myanmar as it is in the States. Santa Clause doesn’t visit Niang’s village. Instead, it’s customary to give gifts like money or clothing to church elders or others involved in the church. Parents will buy their children new clothes, typically the only clothes they receive for the year. Christmas attire is an early decision and a special outfit is reserved early in the year, often in red, white, or green.

“My people are similar to Native Americans,” she says. Sometimes they dance around the fire to the beat of a hand drum or put on traditional clothes, although they’re not as “showy” as they used to be. And although younger people will sometimes indulge in homemade rice wine before the event, they respect the church’s boundaries.

“We celebrate Christmas as Christians, but we always keep tradition,” she says.

Niang’s church hasn’t celebrated Christmas for three years because of COVID. She’s not sure if they will celebrate this year, but she’s hopeful. Meanwhile, she suggests that others in the U.S. slow down, stay present, and “enjoy life” this Christmas season.

Merry Christmas, ပျော်ရွှင်သောခရစ္စမတ်ဖြစ်ပါစေ

Want to help a family experiencing their first Christmas in the U.S.? See what you can donate, or, consider making a financial gift:

Erica Parrigin manages grant writing and communications at World Relief Quad Cities. She graduated from Western Illinois University with a BA in English in 2020. She believes that stories are powerful, and that learning to empathize with other perspectives is the key to making a difference.