The following is a reflection written by John Miller, Immigration Specialist at World Relief Seattle. He is accredited by the Department of Justice to practice immigration law.

Things have felt a little different for me since I’ve been back from Mexico. It’s hard now to read these ideologically-charged news stories about “The Wall” and “The Border” without seeing the faces of the people I met while I was in Tijuana.

I went to Tijuana to meet up with three other World Relief staff members from three different World Relief offices around the country. We convened near the border to partner with a local organization called Al Otro Lado, one of the leading organizations on the ground in Tijuana that provides support to people approaching the US border to apply for asylum. The four of us were selected for this trip because our expertise and credentials with practicing immigration law.

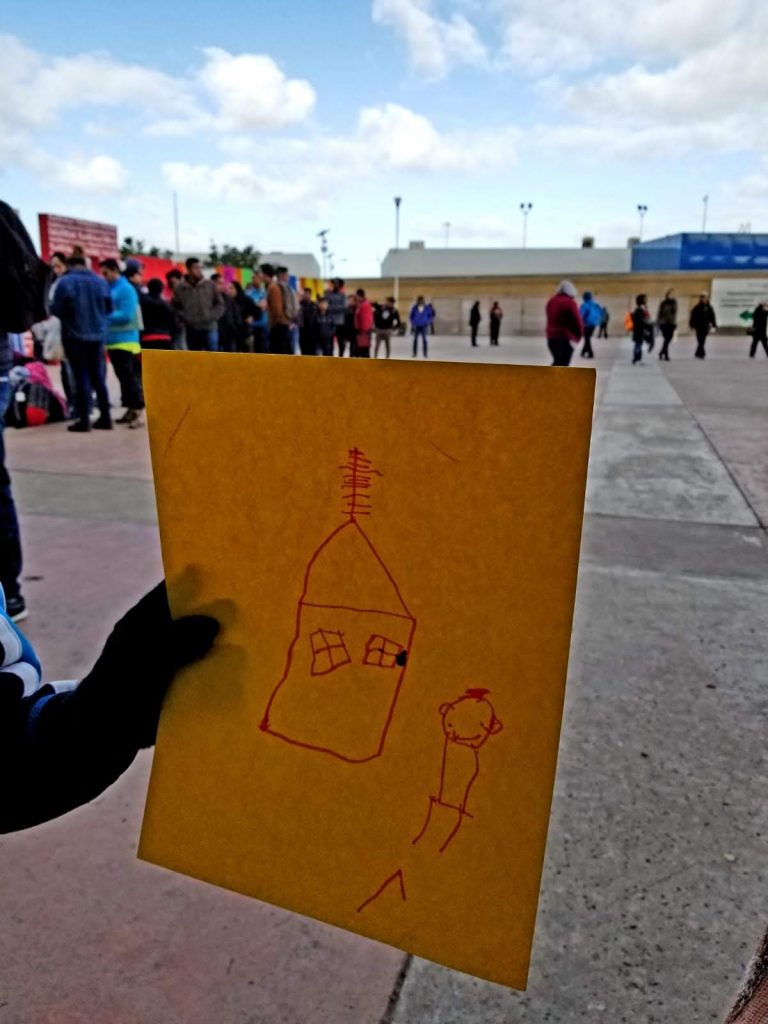

Each morning, we would enter El Chaparral, the infamous plaza in Tijuana, located directly before the border crossing point of entry. I use the word “infamous” because it has essentially become a massive waiting room. But in this particular waiting room, one doesn’t pull a number from a small machine and wait a few hours before speaking to someone. There aren’t chairs to sit on, and there isn’t a receptionist waiting there to help you. In fact, there aren’t staff there to assist you at all. El Chaparral is an uncovered slab of concrete where people from all over the world wait, for weeks or months, before they are allowed to approach the US border to apply for asylum.

Five years ago, if you went to any point of entry along the border to present yourself to US immigration officials and ask for asylum–the “correct way,” as laid out by US immigration law–you would have been taken into the custody of the U.S. government until the next decision had been made on your case. Today, if you go to the border to apply for asylum, you will be told to turn around and put your name on a list to get a number, or even told that you can’t apply there and you need to find another point of entry. You will likely end up in Tijuana, where you would spend the next 3-9 weeks of your life sitting around in El Chaparral, waiting for your number to get called.

This business of getting a number before applying for asylum is a recent phenomenon. U.S. immigration law has stated for decades that any person can approach any border crossing point of entry to apply for asylum. Turning someone away who fears for their life and may have a viable asylum claim is a violation of our own law. This new process also forces people to go through Mexican border officials first in order to gain access to U.S. authorities, which can put people, especially those from Mexico, in increased danger of exploitation and persecution. The physical list being passed back and forth between Mexican and American authorities is ripe for bribery and exploitation.

Our team spent the mornings meeting with individuals and families who were moored in El Chaparral, waiting on their numbers. We gave short presentations on the basics of asylum and what to expect after entering U.S. custody. Next, we met with individuals and families to answer further questions. For each person we spoke with, we gave instructions and directions to Al Otro Lado’s office, so that they could come later to get a free orientation and a free consultation with an immigration practitioner. We spent the afternoons doing one on one consults, learning each person’s story and discussing the exact claim to asylum that the person may or may not have.

One man I met with, who I’ll call Francis, had fled his country in western Africa just two weeks prior to our meeting. When I started our meeting by asking him what country he was from, the whole story came pouring out, the living nightmares that he had survived, and how he escaped. Everything he shared was so fresh. I asked Francis how long he had been waiting in Tijuana. When he told me that he arrived in Tijuana that very morning, it dawned on me: I was the very first person to hear what had happened to him. Here he was, on the other side of the world from his birth place, without anyone he knew, no Spanish ability, no legal authorization to work in Mexico, and no sense of how long he would have to wait before applying for asylum, and I, a total stranger, was the first person to hear his story. I was amazed by his resilience, conviction, and his willingness after everything to stand up for what is true and right. While it was difficult to hear the torture he had endured, I was able to share some good news: the supervising attorney and I both agreed that he had a very strong case. “Your case is very strong,” I encouraged Francis, “and the immigration judge may agree with us that you meet the legal definition of asylum on multiple grounds. Keep moving forward and don’t lose hope.”

I can’t read the news anymore without thinking of Francis’s face: the tears in his eyes, and the strength in his eyes. I think of the Guatemalan family I met in the plaza: the fear in the young mother’s voice, pleading with me to know if there was any way for the family to stay together after passing into US custody, and her fierce, protective love for her kids. I think about the newlyweds from Honduras and the single dad from Cameroon and the nineteen-year-old nursing student from Russia and the minor from Nicaragua who was traveling by herself. These aren’t just news stories about policies, budgets, or political division: they are stories of real people.

The situation is dire, but there is hope. There are organizations like Al Otro Lado who are on the ground, meeting, educating, and equipping the long line of asylum seekers in Tijuana. There are World Relief offices around the country supporting asylum applicants, both inside and outside of immigration detention. And above all, I know that the people I met in Tijuana are some of the strongest people I’ve met, and that gives me hope.

For many immigrants, arrival to America is not the end of navigating the complicated U.S. immigration system. That is why our office has expanded our Immigration Legal Services team from one to three full-time staff who are Department of Justice accredited over the last year. Assisting refugees, asylees and immigrants with work authorization, family reunification, and citizenship are just a few of the services this hard-working team does for newcomers. With your support, we are able to offer these services either pro-bono or at reduced rates to those in need.